It's all connected, right?

how we learn about art, relatedness, ecology and the life of a cell

We had a lot of visual art in the house I grew up in. Our mother was a collector of pieces, especially of local artists’ work. I have an early memory of the two of us looking at a painting hanging in the living room. She was describing how, in composing the piece, the artist invites the eye to explore.

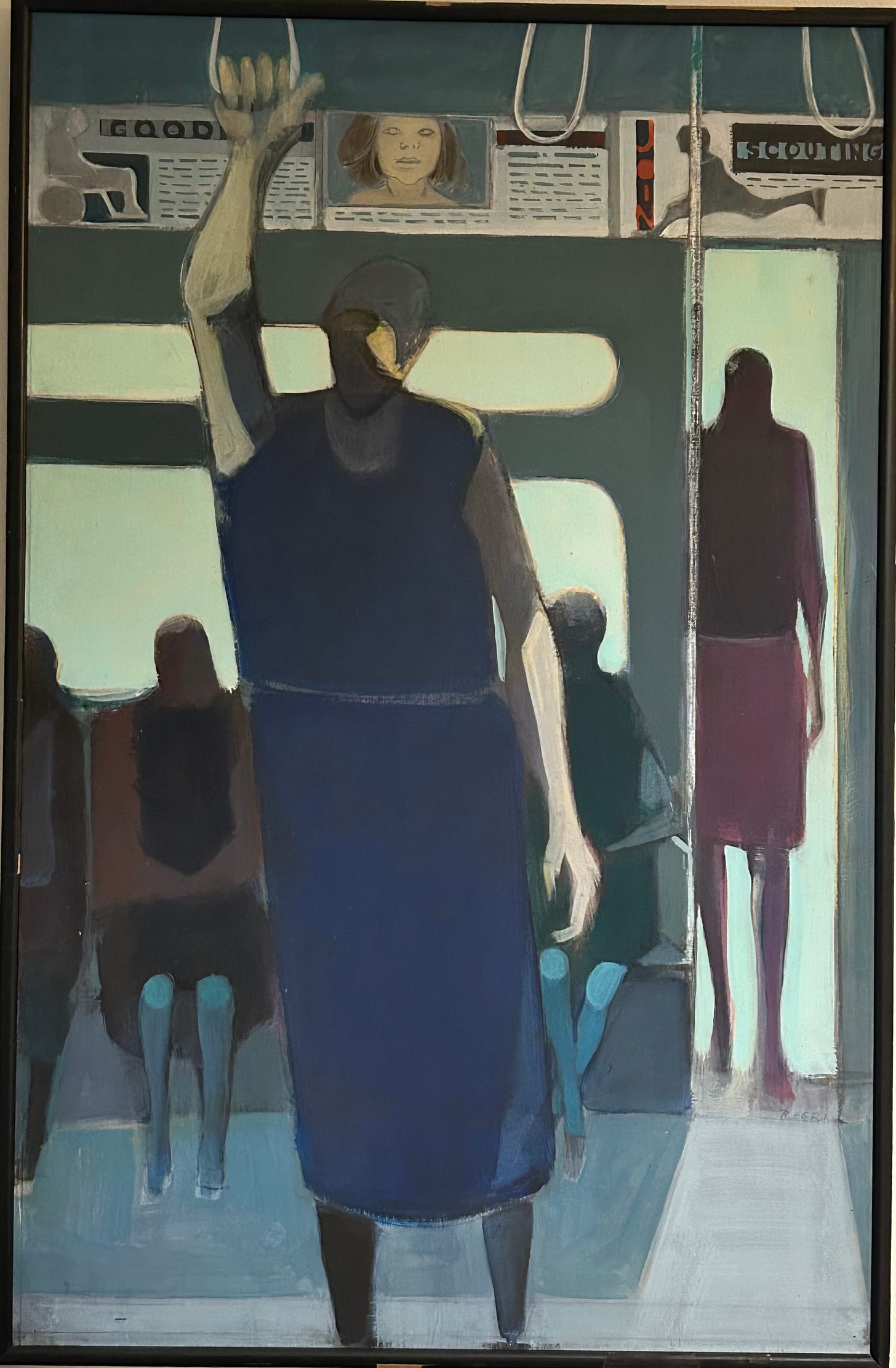

The subject above is a group of women commuting on a metro system. The outside light comes through shapes running horizontally and vertically. Mom would point out the brightness of the standing woman’s forearm and side of her face that catches her attention, then the hand straps and advertising pull the eye across to the bright vertical door and the shape within it. The eye moves between shadow and light, from background to foreground, which is part of the genius of a good work of art.

This and other such instruction formed my early lessons in the art how elements are put together and work together — composition.

Same applies to the craft of poetry. Mom’s yellow legal pads, where she worked out her latest verse, were a flurry of cross-outs and scribbled phrases that were summarily struck through, lists of alternative words, arrows moving phrases from here to there, re-writes and re-writes of re-writes. Sometimes for pages and pages.

I knew what she was doing. She was striving for that perfection of poetic conciseness where every word was doing its work, with nothing extraneous just hanging on — nothing more was needed to convey the thought, and not a jot else could be taken away.

Like most humans with an artistic bent, she enjoyed moving toward that state of perfection, even if she rarely, if ever, felt she arrived.

We were raised in a household with lots of J.S. Bach in the air. Mom played his short pieces on the piano, and there were recordings on the hi-fi — Glenn Gould, the Brandenburg Concertos with Pablo Casals conducting the Marlboro Festival Orchestra. Here again, Mom’s voice is there in an instructive moment, pointing out how a canon works, with different voices of the orchestra taking turns with a common theme — another example of how things work together.

See how it all fits together? See the patterns? See how everything depends on everything else? Look how it all works!

I remember these kinds of thoughts when I was introduced to the word “environment” in I think the fifth grade. Or maybe is was “ecology.” Anyway, a new word about interconnectedness. Our class was studying an annotated picture of life in and around a stream, and we would go on to learn about the food chain, the water cycle.

In seventh grade science we would learn about symbiosis — the long-term biological interaction between two organisms of different species living in proximity to each other. Then eighth grade geology — how earth formations affected human civilization. I mean, it just went on from there. Once you learn these things, you start thinking about them and seeing them over here and over there. Everywhere.

These are all examples of early learning — about art, about systems, about organisms and organizations. I was learning about how interconnectedness works. An early college-age read was Lewis Thomas’ Lives of a Cell (Bantam Books, 1974), a set of 29 essays written for the New England Journal of Medicine. The final entry compares the Earth to a cell, and Earth’s atmosphere to a cell membrane — recycling our oxygen and water and at the same time protecting all of us from the chaos of ultra-violet light, bursts of charged particles from the sun, and meteorites. Said Dr. Thomas:

For sheer size and perfection of function, it is far and away the grandest product of collaboration in all of nature.

Unfortunately, Homo sapiens has had an outsized influence on this membrane. Turns out that while the atmosphere has been protecting and nurturing us, we have been fiddling with its ability to do its work in this biochemical composition.

This weekend I will have the opportunity to help facilitate an intergenerational dialogue about the Anthropocene — a non-official designation for this period of Earth’s history in which humankind has made its mark upon, well, everything. My October 2 post was about this event if you want more details.

Small groups representing diverse age cohorts will discuss their responses to two prompts:

Briefly describe one life experience that has strongly affected your feelings toward the natural world.

Imagine that you are talking with a future descendant or another person living in a time when humans no longer disrupt Earth’s climate and biosphere. What would you want to tell them and/or to hear from them?

There might be common themes, differences across the generations and some surprises. I will let you know what they say.

The event is intended to invite people to reflect on how we got to this point, how we feel about it and what we think might be done to get us back to a more symbiotic relationship with all the other life on Earth. And to do all this without lapsing into blaming all industry for the cause, and beseeching of our political and industrial leaders for the solution.

And what keeps hope alive during this kind of discussion? What keeps the mind’s eye moving and exploring what is before us? How do we keep from landing on that point of oblivion where the ominous dark chemtrails converge on the setting sun of humanity’s rapaciousness?

The possibility that meaningful change happens in small increments, through modest, individual efforts?

That each of us can take on our proportional responsibility of a larger effort to repair the world?

Perhaps something the current system that got us here can not possibly give us, but that a new generational reckoning will see and take action on?

Notes

World Permaculture Association

David Brailsford’s concept of incremental improvement

An article about Tikkun Olam, repairing the world

This is lovely. I kept thinking about the mosquitos that ate my legs when I was 6...I had a really bad allergic reaction and my legs got so swollen that I couldn't walk. My mother towed me around in a wagon until the allergy symptoms subsided and I was restored. From that point on my relationship with nature was quite restrained and avoidant. But then, there's sunrises and sunsets and total eclipses and orchids and teeny tiny tree frogs. And the beautiful, beautiful desert and the sounds of waves crashing that I could hear at night in bed when we summered in Fire Island. I don't immerse myself in nature, I never have, but I do have gratitude for the immensity of creation and terrific sadness at how humans have taken whatever they wanted and left this planet so much worse off than when we came on the scene. Non-human animals are so much wiser that we will ever be. And that's a damn shame. xo

I admire your mother's instruction and your family's penchant for learning. While some of the same instincts and appreciations existed in my family of origin, somehow I have no recollection of there being an inclination to share that kind of instruction. Maybe I just wasn't paying attention.

I look forward to hearing the outcomes of your event and can think of no better way to explore possibilities than an intergenerational conversation. In recent past I've come across a handful of. manifestos, the most potent of which (for me, at least) was revealed in this podcast. https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/farmerama/id1031542491?i=1000636531889

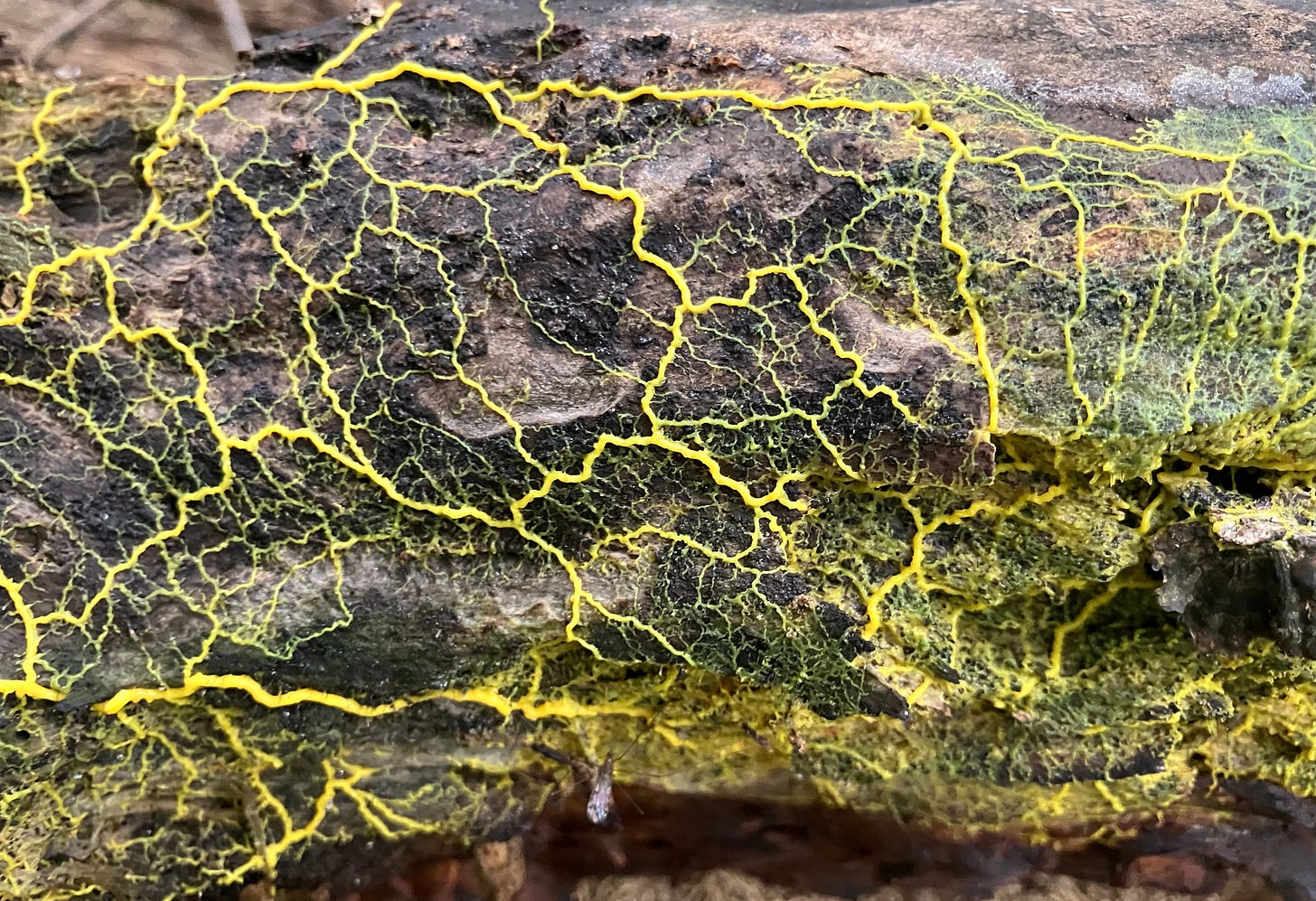

Yes, it's ALL connected! The tree rot / lightning photo is amazing!