My visit with Edward Gorey

or How I Got a Cloth Frog

Nineteen-seventy-three. I was working a summer job in the Brewster Ice House on Cape Cod and living in an attic rental in Rock Harbor, Orleans. I went to visit Edward Gorey (American writer, artist and illustrator 1925-2000) at his summer house in Barnstable. I was 19, and this would be a highlight of my life to date.

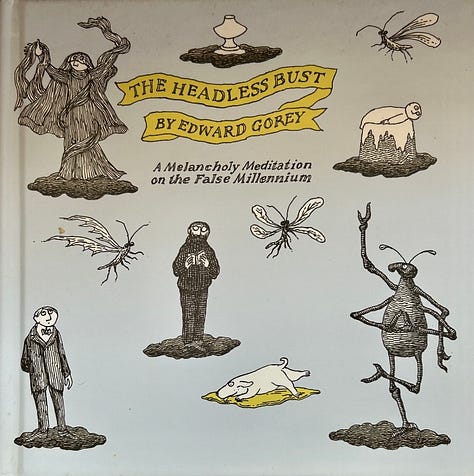

This was also the year Gorey designed sets and costumes for a Nantucket theater production of Dracula. The success there would set the play on a trajectory for Broadway in 1977, starring Frank Langella. Gorey won a Tony Award for costume design in 1978. His pen and ink drawings would famously be used for the opening sequence of the PBS series Mystery! since 1980.

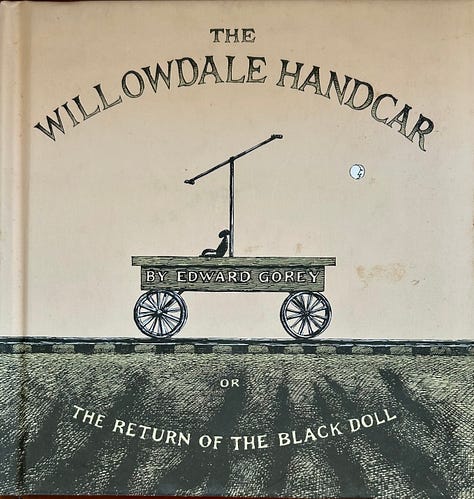

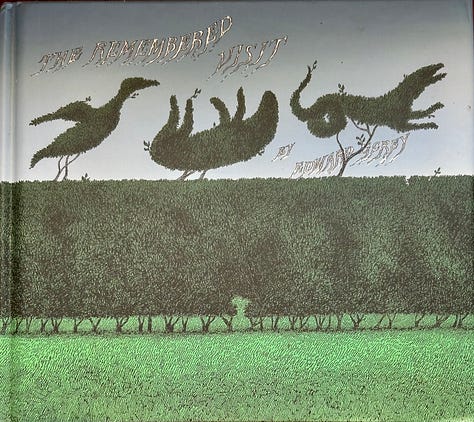

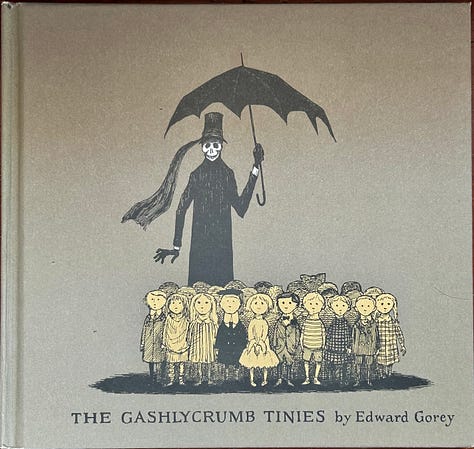

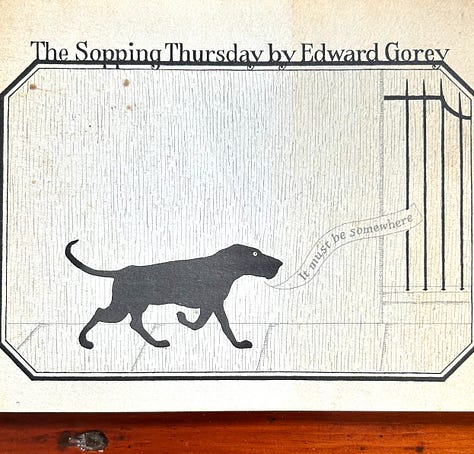

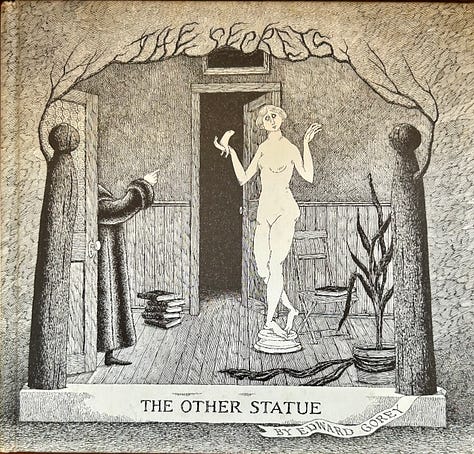

I knew none of this at the time. I had been a fan of Gorey ever since my sister Martha brought home little books of his that she had borrowed from a friend at Oberlin College. At that time, Gorey’s illustrated stories were published in limited editions of 1500, and sold through the eclectic and literary mecca — Gotham Book Mart at 41 West 47th Street in New York City.

Here is how things worked when one was a late teen before the internet. A collection of seventeen Gorey books, Amphigorey, came out in 1972. The dust jacket flap said simply that he “divides his time between New York City and Cape Cod.” I looked him up in the phone book (never mind if you don’t know what that means) and gave him a call. I don’t remember the exact conversation. I told him I was a fan, and that I would like to meet him. He invited me over for tea and we set a date. He gave me directions which I wrote down on a scrap of paper (never mind if you don’t know what that means) — Barnstable exit off Route 6, turn right, bear left at the cemetery, green frame house on right.

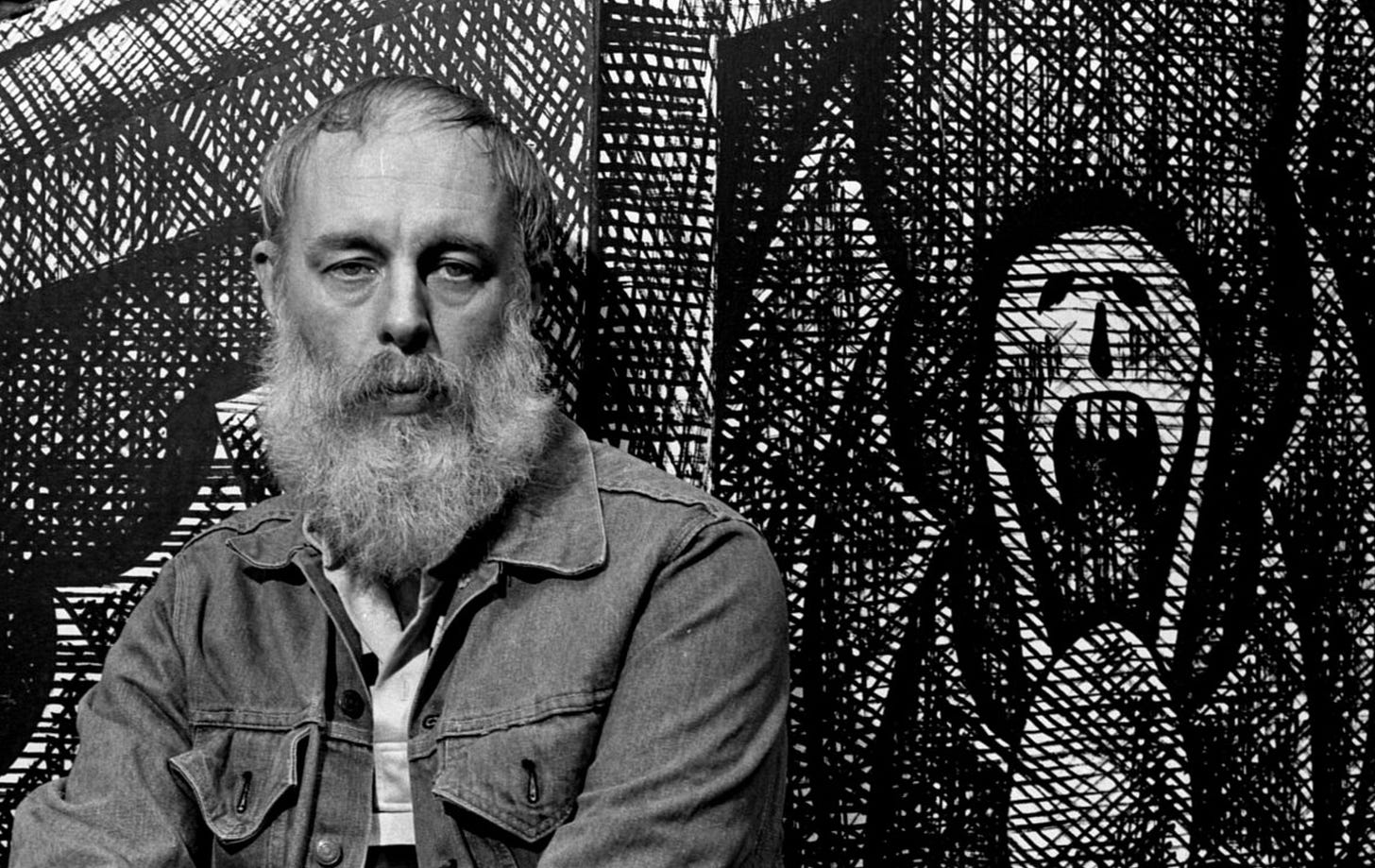

I admit, I had some preconceived ideas about Edward Gorey, based on his dark humor, meticulous drawings and Edwardian settings for his tales. In my mind he was short, dark-bearded with sunken eyes and a lost smile. He was British and his name was in all probability a pseudonym. He might even be deceased. Remember, he was not a figure of any popular renown at this point.

His kind and deferential manner over the phone and mid-west accent disabused a few notions. When he strode into the room I knew that every notion needed updating.

I am reminded of a quote from The New Yorker on a dust cover from a 1999 volume:

Many of Edward Gorey’s most fervent devotees think he’s (a) English and (b) dead. Actually, he has never so much as visited either place. But his work has imprinted itself on the American consciousness as something from long ago and far away.

I took notes after the visit and used them to fashion an account I wrote in 1974 for my college literary magazine. It is titled The Visit, or The Reformed Umbrella. I will quote a few passages here.

I had always presumed authors in general to be inaccessible, and I imagined Gorey, in particular, to be indifferent toward social encounters; perhaps even resentful. But he had invited me to meet him with a voice that sounded like that of a cheerful young scholar and not like the shadowy, silent man I first imagined.

His cousin, a kind woman, met me at the door and said “Ted” would be here soon. I waited in the sitting room and helped his quiet nephew work on a large jigsaw puzzle — a winter scene by Pieter Breughel. The quiet nephew said his uncle worked on lots of different ones. Indeed, there were many boxed puzzles lying about the room.

Soon he strode in, hand extended. “Hi, I’m Edward Gorey.” He was about my height and wore a light T-shirt, madras shorts and a pair of green beach sandals. He appeared to be fifty or so. His skin was positively pallid, his hair short and receding. Beneath his broad forehead his calm blue eyes stood out wide and expressive. His untrimmed beard was the color of dust and snow.

As we worked on Breughel, we talked about his years at Harvard, the Cape, our favorite graveyards, a literary event he recently attended in Wellfleet, and his cats (who lived upstairs in his studio). Naturally, as a fellow writer I was curious about his creative process, his sources of inspiration, the meaning of it all. That part of the interview was brief:

Me: Would you mind me asking a few questions about your work?

Gorey: (diffidently) Oh, I really wouldn’t know what to say.

Shortest literary interview ever.

But we easily got on to other topics. He gave me a tour of the house which culminated in the attic, where the cats lived.

He paused at the door to the stairs that led to the attic room. He turned to me, his eyes focused at a point on the wall just above my head. “This is where I keep everything,” he said. I gazed up the stairs to meet the eyes of four cats looking down upon us with great interest.

Once at the top of the stairs I was in a large and very cluttered room. Beneath a large window just to the left was placed a broken piece of a tombstone. It read: HERE LYES BURIED THE BODY OF.

We walked about the territory with him telling tales and recollections and me taking it all in.

Everywhere I looked there were Things: trinkets hanging from nails in the bare beams of the walls; rows of colored bottles; a collection of ceramic jars; a large bowl filled with rags; a collection of glass telephone pole insulators; stacks of china plates; more books in shelves along the far wall in tumbled stacks front of the shelves and piled in a rocking chair that faced a window; a row of brightly colored beasts of possibly Mexican origin lined up on a settee. From the rafters hung three beautiful huge bunches of dried flowers, and centered in front of the far wall hung a small wicker cage containing an armless, featureless black doll, slouching to one side. One very large Chinese dragon hid in the eves. But the most conspicuous by sheer number were the several dozen rice-stuffed cloth frogs that lay limp and still on the rafters looking out the window.

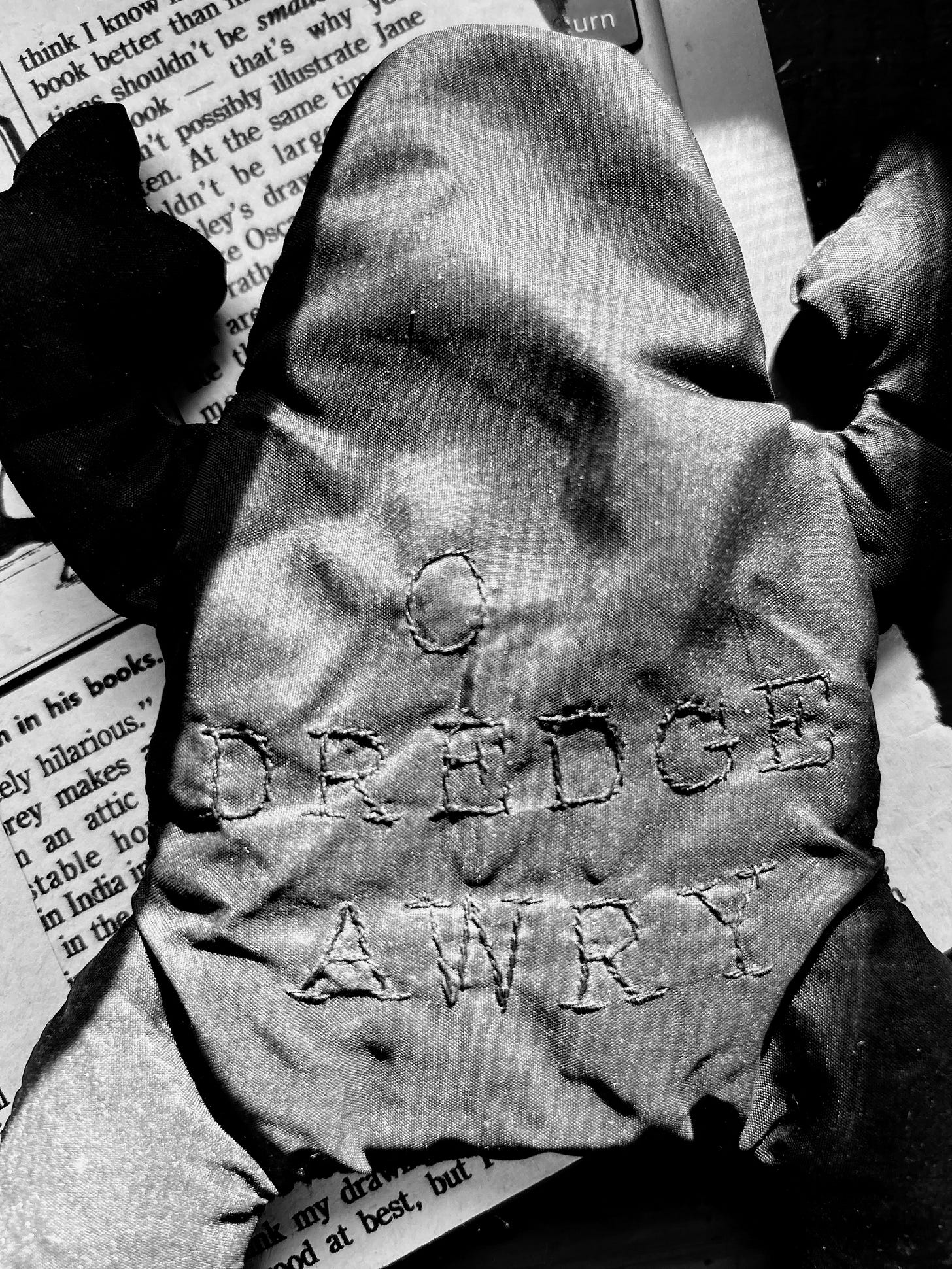

“I make them out of old umbrellas,” he explained from a large chair in the middle of the room where he sat stroking one of the cats, an orange tabby named Agrippina. “If you walk down Fifth Avenue after a windstorm, you are bound to run across a fine collection of umbrellas turned inside out and discarded. I salvage the material.” He spoke of his frogs with a childlike enthusiasm. “I saw ones like these in a cheap gift shop and I said to myself ‘I bet I can make these. I bet I can can make ones better than these.’” He rose from his chair and reached up to one, his favorite. He explained that he often stitches messages on the stomachs of the frogs. This red and black frog said: LIFE IS LIFE.

I do not remember how this happened. I must have mentioned my sister Pat’s upcoming birthday at some point. He said he would make a frog for her, and asked what colors she liked. The purple and orange frog would be inscribed A BIRTHDAY FROG. How I got two frogs in the bargain, again I can’t say, but he said he would make one for me. I asked for the Fifth Avenue umbrella style.

Maybe three weeks went by and the phone rang at my domicile in Rock Harbor. I can confidently say this the best phone greeting I had received to date, and probably ever.

Hello, Stewart? This is Edward Gorey. Your frogs are ready.

I would see him once more, briefly, when I picked up the promised frogs. Pat still has her Birthday Frog. Mine keeps me company at my desk.

Gorey's art work is still used as the intro to Masterpiece Mystery.

Fascinating, Stew, and what a memory to have, not to mention the frog(s)! I smiled with you at the process you took to meet Mr. Gorey, and at how simply the connection was made. I was also reminded of this piece, the beginning of which which stood out for similar reasons.

https://bigthinkmedia.substack.com/p/tap-into-the-hemingway-effect-to

Does the frog have a name?

Thanks for sharing this delightful bit of your history.