Trading in my iPhone for a Model 500

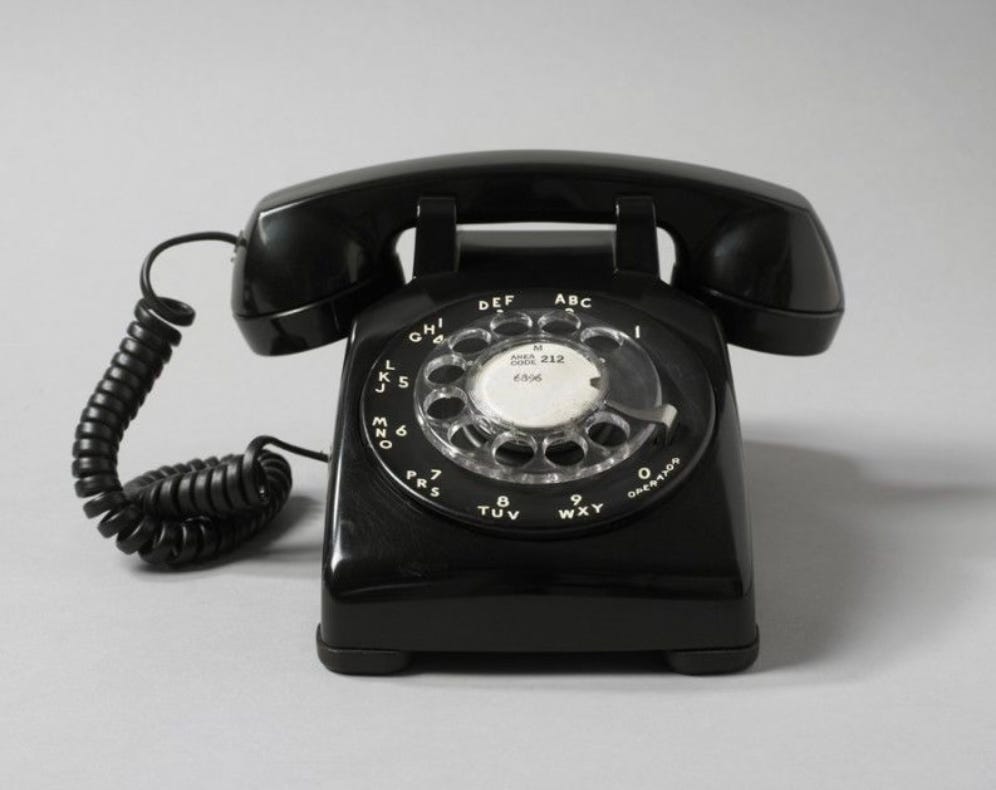

the black Western Electric rotary phone

From my side of the fence, I can tell that my next door neighbor is home from work. I hear her talking, every word as clear as if she were shouting right over the fence to me. In fact, she is about 70 feet away on the other side of her lawn, facing away from me, with what appears to be small soup bowls on her ears. I’m sorry. My mistake. She is wearing headphones that are connected by Bluetooth to her phone.

I am not sure why she is shouting. If the other person were sitting in their yard, their voices would be, I dunno, conversation volume.

I will say right here that I am sensitive to sounds in certain contexts, in the same way that some people can’t wear wool.

For those who don’t remember, or who never experienced the Bell Company phone, here is a summary of our family phone 1955-1968.

There were no plugs. The stout black cord came out of the wall, ran across to the desk, and went into the side of the phone. The cord was maybe 4 feet long. The spiral line from the base to the handset was maybe another 3 feet. Not surprising then that the phone never left the room. There were two phones and one screen (the TV) for a family of five. The screen also never left the room. Why would it?

The handset had a speaker end and a receiver end. When you spoke into the speaker, you could hear yourself in the receiver, providing you with a kind of feedback loop for your voice.

I also remember from those old phone conversations that two people could talk over each other and be able to hear both voices simultaneously. Apparently, these old analogue phones were able to send and receive signals at the same time. So when my buddy and I talked over each other, we could hear each other, and quite easily get back on track.

Compare that to a cell phone conversation. If two people talk at once, one voice gets clipped and the conversation stops. Then this:

“You go.” “You go.” (said at the same time)

Pause

“No you.” “No you g…..”

Longer pause, while each waits for the other to start.

“OK, what I was going…” “What I was say…”

We have gotten used to this awkwardness. It wasn’t always this way. It is part of our new technology.

Analogue phone conversations had the ease of real time; the signals flowed smoothly along copper wire, back and forth at the speed of electricity.

Digital communication with cell phones, on the other hand, are subject to a latency effect — a slight pause between the speaker speaking and the listener hearing. Cell communications also require the voice to be digitized and compressed into “packets” and the exchange is monitored by a set of algorithms. When two voices clash, the algorithm can interpret this as an echo, and clips off one of the voices.

Add soup bowls and there is another problem. When wearing headphones, it’s hard to get a sense of how loud your voice is in the environment. Add to that the tendency to adjust the volume of one’s voice according to how far away the other person’s voice seems to be. That makes sense, right? If I’m walking side-by-side, a conversational pitch is adequate to hear and be heard. But talking to a person on the other side of the street requires a little more volume to compensate for the distance, and other external noises.

My theory is that in my neighbor’s conversation, the person at the other end sounds as though they are at some distance.

When I am wearing even my humble AirPods, it is easy to forget that my voice needs to travel only from my mouth to the receiver in my ear — about 4 inches. Not a lot of bellowing needed.

This is as good a time as any to make my public service announcement. When the human ear is straining to hear something, there is a tendency to limit the movement of the head and to hold it still. Bird watchers know this. We humans are able to detect whether a sound is coming from our left or our right by the minuscule difference between the sound hitting one ear and hitting the other.

The danger comes when we are driving a vehicle, where we rely on the back and forth motion of the eyes and head to continually scan the path of our movement and check mirrors. I’m not sure what the solution is except not to wear ear pieces while driving. Please comment below if I am wildly wrong about this. Or even a little wrong.

It would be folly, of course, to trade in my iPhone for any analogue device, just as would be trading in my car for a horse. I guess this is just a moment of nostalgia, back to a simpler time when we all took phone calls in a designated room, tethered to a big block of phone. And if you overheard someone else’s conversation it was because you were sitting in the same room.

Technology has untethered us, but in the process it has also reshaped how we listen — and how we’re heard. Maybe the lesson isn’t to go backward, but to remember that even in a wireless world, the human voice still longs for clarity, presence and connection.

Next week:

Extending the shelf-life of bitterness: is anything gained by carrying grudges and grievances?

Ah, the pitfalls of modern technology. And how often I've been confused by the sound of someone speaking in a store, thinking they're directing their comments at me. My mouth opens in the attempt to make some sort of polite response, only to discover they're wearing headphones. 🤦♀️

An old phone would be comforting every now and then, like a bowl of Campbell's tomato soup and a grilled cheese sandwich. But I wouldn't want it regularly.