Words, words and 27 years of walking

what a philosopher, a playwright and a paratrooper tell us about wanting to know

I am in the process of reading two books. Some nights I pick up one, some nights the other. One is Big Dumb Eyes by comedian Nick Bargatze. It is not as funny as his stand-up routines, but it’s funny enough, the way he tells stories about his life and how he got to be the way he is.

You might be a little nervous opening these pages, because I am very on the record about not liking to read books, about how every book is just the most words. How it never lets up and there are just more and more words until it’s like, “What are you talking about? Please, just make it stop.”

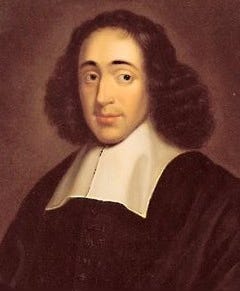

The other is The Ethics and Other Works by Benedict de Spinoza, edited and translated by Edwin Curley. Curley explains in his introduction that Spinoza’s whole career as a philosopher was based on his hope that “the pursuit of knowledge would lead him to discover the true good.” Indeed, The Ethics, his crowning achievement is, as Curley puts it:

…a systematic attempt to work out, in a geometric fashion, his views on the nature of God, the relation between mind and body, human psychology, and the best way to live.

I would love to see this guy’s resume. Seriously, this is a man who was ex-communicated from his Jewish community in Amsterdam for his “evil opinions” but was undeterred in his pursuit of truth.

You have to admire his tenacity. Even so, he delayed publishing The Ethics out of concern about how the public might react to it. The work was published posthumously a few months after he died in February 1677 from a lung illness “probably aggravated by the dust of the lenses he had been grinding in order to support himself.” In a way, his philosophy became the very lens through which he sought to bring the truth into focus.

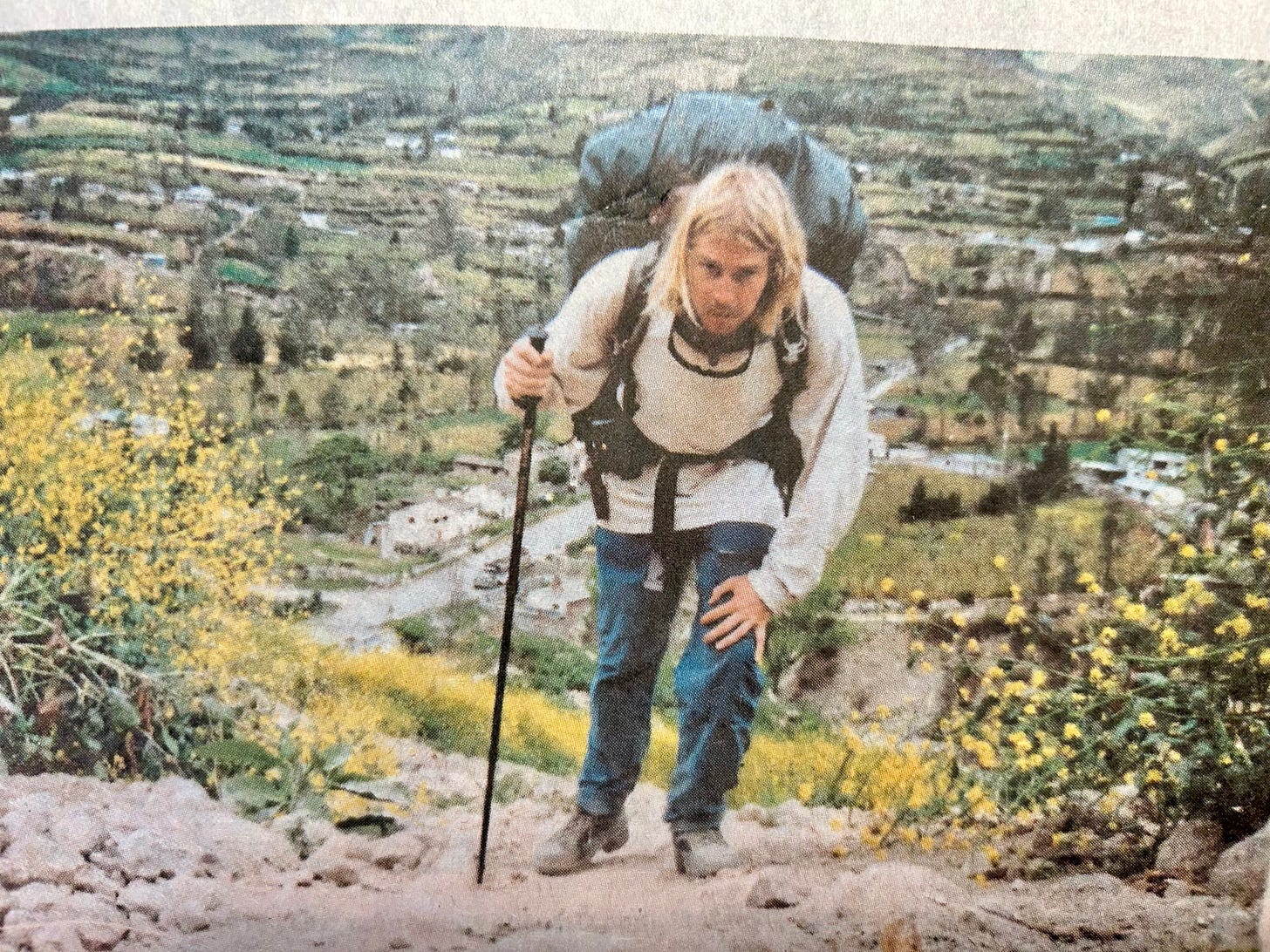

Speaking of determination, there was a recent story in the Washington Post by Sydney Page (December 8, 2025) about Karl Bushby who has been walking from Punta Arenas, Chile to his home in Hull on the east coast of England. It started as a barroom bet. As Bushby explains, “Suddenly, it became a challenge. The conversation gathered steam until eventually I did the math and thought, ‘This is doable.’” He made the bet in his late 20s. He is now 56. It’s been 27 years, and he has 932 miles to go, from Hungary to home.

He made only two rules:

I can’t use transport to advance and I can’t go home until I arrive on foot. If I get stuck somewhere I have to figure it out.

Here are some examples of challenges he had to “figure out” how to deal with: a stomach infection in Peru; crossing the frozen Bering Strait; being detained for 57 days for entering Russia at an incorrect border; and swimming for 31 days across the Caspian Sea to avoid re-entering Russia or Iran. To name only a few.

Bushby got his fitness, endurance, and resilience as a paratrooper with the British Army. He also got the urge for travel and exploration. I am sure he learned a lot about himself, how to pace himself, how to deal with loneliness. But the big piece of learning — the “real shocker” as he put it — was this:

99.99 percent of the people I’ve met have been the very best of humanity. The world is a much kinder, nicer place than it often seems. It has just continued through every culture in every country — the overwhelming kindness of strangers.

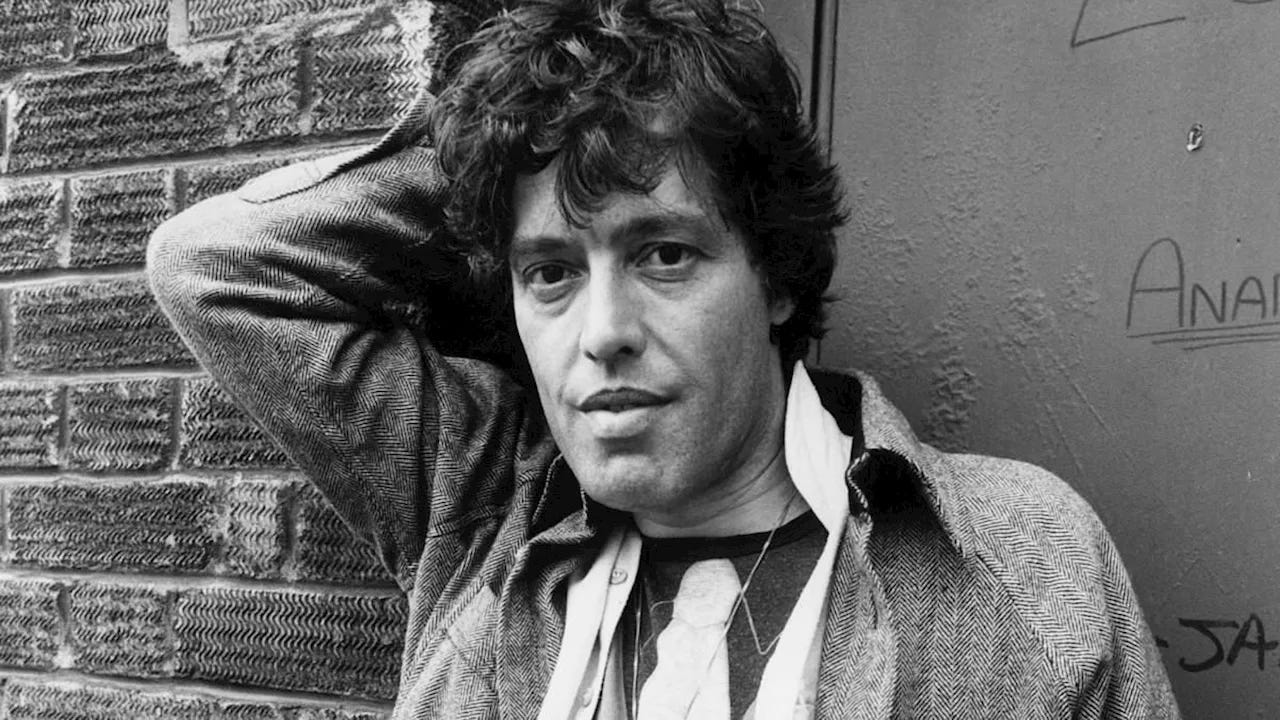

The struggle to better understand the self, each other and the circumstances around us is a theme in many of the plays by Tom Stoppard. The playwright passed away a few weeks ago. I took a pause from my two books to re-read Arcadia, possibly the most interesting, beautiful, funny and tragic play I have ever read.

My favorite quote is spoken by the character Hannah, a dedicated and relentless researcher.

It’s the wanting to know that makes us matter. Otherwise we go out the way we came in.

This is a recurring theme for Stoppard, one he first explored in his first blockbuster play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (1966). In it, the two minor characters from Hamlet—dispatched to “glean what afflicts” the melancholic prince—struggle to make sense of the baffling situation they’ve been drawn into. Here are a few memorable lines, spoken by Rosencrantz (or perhaps Guildenstern).

There must have been a moment, at the beginning, where we could have said -- no. But somehow we missed it.

Words, words. They’re all we have to go on.

Life is a gamble, at terrible odds. If it were a bet you wouldn’t take it.

They never really get answers, and meet their demise as they did in Hamlet, off-stage at the very end.

It’s the wanting to know that makes us matter. Otherwise we are going out the way we came in. Why does it seem that the world is mostly interested in legacy, what we have done, what we have accomplished: the resume, the biographical sketch, the obituary. Or the standard Washington DC line for someone you meet at a party: “So, what do you do?”

I have also heard “What are you working on?” which is a little more expansive. So are “What are you trying to figure out?” and “What’s the big question you are trying to answer?” The risk is, of course, that these questions might seem too forward for someone you just met, and they might suddenly have to excuse themselves to freshen their drink.

But I still ask myself these questions, like, all the time. It’s wanting to know – to really understand.

Is it possible to be in love with a quote? Love at first sight, even?

"It’s the wanting to know that makes us matter. Otherwise we go out the way we came in."

I've leaned into curiosity for more than a year now. I'm trying to figure out if there's any reason to choose anything else.

Loved how you tied all these lives into one story, Stew, and the glow of inspiration their tenacity leaves behind.

Such a great read--and a truly remarkable juxtaposition of characters!!