"Again, without evidence"

is critical thinking even a thing anymore?

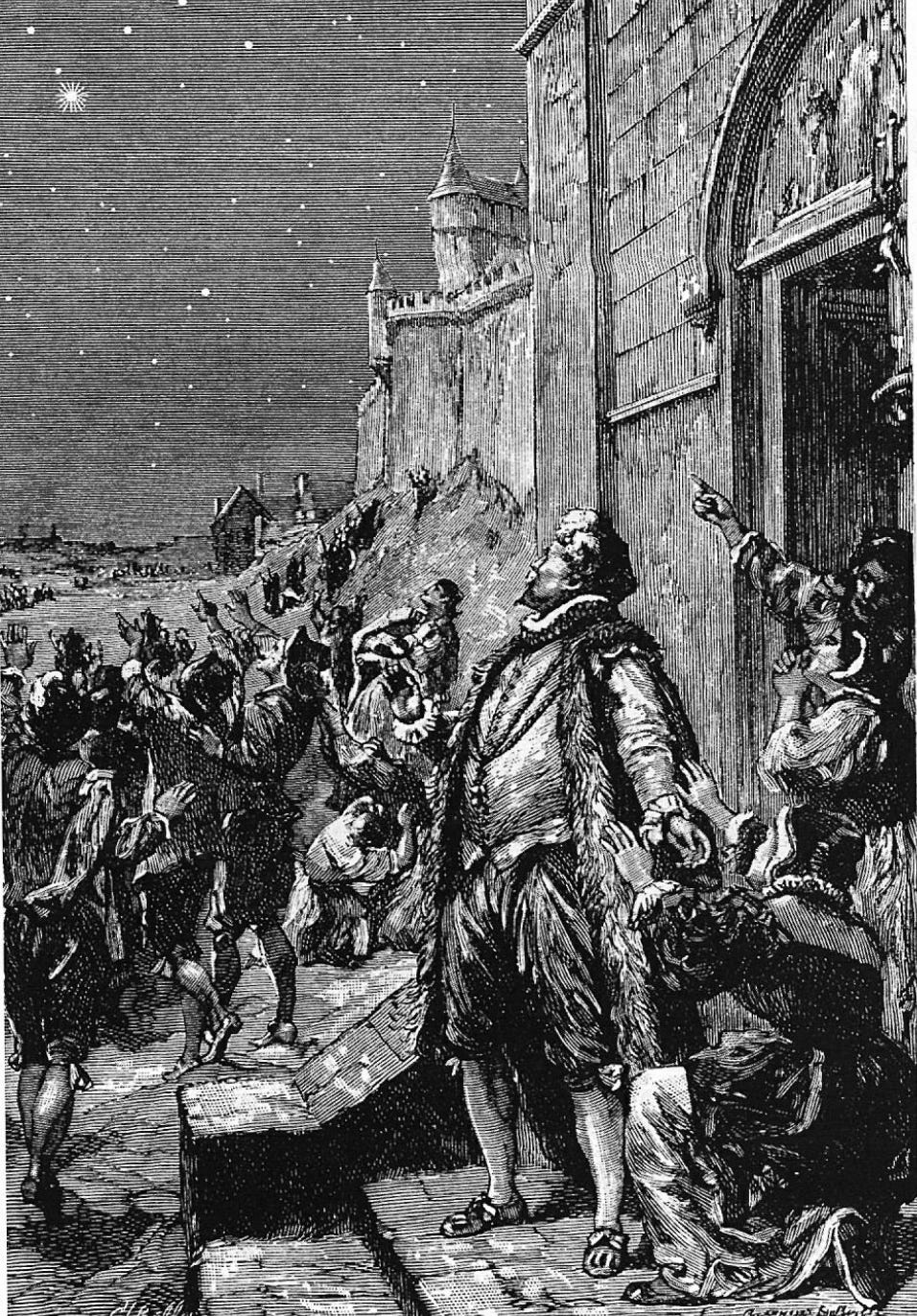

It would be difficult to overestimate the impact of the supernova that appeared in the sky in November 1572. For a brief time this “new star” in the “W”-shaped constellation Cassiopeia was bright enough to be visible by day. Up until the time of its first appearance, it was generally believed that all matter beyond the orbit of the Moon was immutable.

Below the orbit of the Moon was where all the living and dying happened; beyond was unchanging perfection. This was part of the medieval model of the universe. It was derived from Platonic and Aristotelian principles, and held sway for a millennia, supplanted only when a better model took its place; one that could explain the most phenomena in the easiest, most economical way.

A claim that is stated without any evidence is a thing nowadays. This phenomena got me thinking about what our current culture values in terms of “knowledge.” And why I am compelled to put “knowledge” in air quotes.

To explore further, I went back to basics, which in my case is the Middle Ages, a period in history that morphed into the Renaissance around the time of the supernova mentioned above. I remember reading C.S. Lewis’s The Discarded Image as an undergrad, and being struck by so many ideas new to me– including a description of the medieval model of everything which was extremely ordered and predictable, with a place for everything and everything in its place.

Back then, when not everyone could write, authors were held in especially high regard. The word ‘authority’ is a remnant of that status.

Back then, it was reasoned that if humans lived on earth, and the gods (or God) in the heavens, there must be something living inbetween. (And don’t say “birds” because they don’t fly higher than the mountains.) These dwellers were the Longaevi — the longlivers — “marginal, fugitive creatures” (according to Lewis), which included fairies and elves, faunas and nymphs, Tom Thumb and Robin Goodfellow, the spoom, the puckle, bull-beggars, and others.

This is fanciful stuff that added “a welcome hint of wildness and uncertainty into a universe in danger of being a little too self-explanatory,” Lewis suggests.

For example, in the Middle Ages different types of knowing were clearly delineated. Remember the medievals were influenced by Aristotle, and his ideas were in turn developed by Thomas Aquinas. As a medieval, I would find five ways to respond when considering a proposition:

Doubt (dubitatio)— I suspend judgment. I can’t say yes to this claim. “I don’t know if ghosts exist.”

Opinion (opinio) — I can ‘say yes’ to the claim. I thus give assent, but not with full confidence. “This looks like a good investment, but I might be wrong.”

Faith (fides) — I give firm assent, because of some authority, even if there is no demonstrative evidence. “I believe in life after death.”

Knowledge (scientia) — I give firm assent, and my “yes” is founded on evidence that I find convincing. “The sum of the angles of any triangle is always 180 degrees.”

Understanding (intellectus/sapientia) — This is where I would have a direct grasp of a rationale (such as knowing why the angles sum to 180) or of a divine truth.

The hierarchy is elegant, comprehensive and self-evident. It enables people to clearly identify and communicate their standing toward any given proposition.

A problem for us nowadays is what Daniel Kahneman points out in Thinking Fast and Slow: given two mental activities, our brains tend to select the simpler of the two. Choice of two questions? Let me answer the easier one. Choice of going with my gut reaction or reasoning out the best decision? I will go with my instinct, and then use my reason later to justify the choice I made. When I have more time.

What I mean is, the pace of taking in information and communicating nowadays requires shortcuts. Not only do we need to be fast, we need to keep and hold the public gaze. And, unlike the Middle Ages, when there were few authors, now everyone potentially is an author.

We have wound up in a twitchy tangle of micro-burst messaging designed to titillate, outrage, amuse, click and purchase.

Time to state my opinion, and offer reasons for my hesitations? Not really. How about I just hold forth on how I feel?

Time to give actual evidence, or ask the reader to follow a train of reasoning that is more than three cars long? Sorry, no can do.

I know: let’s fold together opinion, faith and knowledge in one big category! That way we can simply animate people to action with assertions of truth:

“All immigrants are criminals.”

“Trillions of dollars are being taken in on tariffs.”

“Anti-depressants cause gun violence.”

So much easier for the current media environment.

What might the 2025 counterpart be to that supernova 453 years ago? Something that would send a message the world over that the model we have needs to be discarded?

But such evidence would involve looking up at the sky. Who does that anymore?

Notes

The Supernova of 1572 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SN_1572

Long-form piece on how outrage in particular behaves like a virus by Scott Alexander https://slatestarcodex.com/2014/12/17/the-toxoplasma-of-rage/

Really loved the supernova metaphor, Stew. Such a cool way to frame a shift in how we see the world (and really, can you imagine??). The whole comparison between medieval ways of thinking and how we process information made me wonder how often I pause to ask what kind of knowing I’m using—just gut reactions most of the time. Then I overthink afterwards! 😅That breakdown of doubt, opinion, faith, etc. was super clear and kind of makes me want to slow down. That said, do you think anything’s been gained in this shift? Like, yeah we’ve lost some rigor, but maybe there’s something valuable in how open and accessible things are now? Except for the messy part.